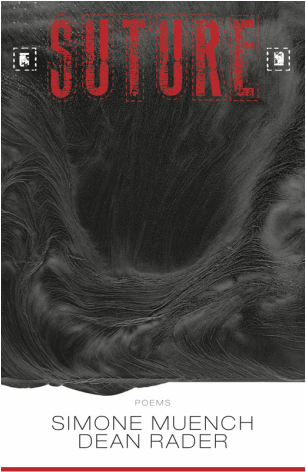

S U T U R E : T H E F R A N K E N S T E I N S O N N E T S

by Simone Muench + Dean Rader

|

SAMPLE FRANKENSTEIN SONNETS FROM SUTURE

|

_____________________________________________________________________

|

SIMONE AND DEAN DISCUSS THE SUTURE PROJECT

On Collaboration: The Frankenstein Sonnets (from Zyzzyva, volume 101, Fall 2014)

Simone Muench & Dean Rader

This particular collaboration began in January 2013. Initially, we contemplated several ideas including a correspondence-type of collaboration in which we would trade individual poems; however, we wanted our voices intertwined in a way that would be indistinguishable to the reader: neither a Rader voice or a Muench voice, but a new third-bodied utterance spawned by differing styles. We elected on assembling the poems stanza by stanza, using this more integrative approach in an effort to co-join the presumed chaos of collaboration with the formal constraints of the sonnet. Because collaboration is frequently perceived as chaotic and can often suffer, as the luminary Michael Anania notes, from the “bipolar diffusion or poetic jiu-jitsu contending egos can produce,” we resolved to work within the framework of a highly structured form—specifically, the sonnet.

We refer to our poems as "Frankenstein Sonnets" because we cut lines from other poet’s sonnets, then graft our own sonnets onto the originating skein of flesh. When we first decided that Frankenstein would be the umbrella concept for our sonnets—the suturing together of other’s flesh/words with our own—we addressed how much should be cannibalized and how much should be our own. We ended up being minimally cannibalistic, deciding only to swap lines from other people’s sonnets to employ as the first line (which also serves as the title). So, for example, Simone would provide Dean with a line and we would then write the first stanza initiated by the provided line, thus establishing the first rhyme set as well as the type of sonnet, before forwarding it to the other person who would complete the second quatrain and then send it back to the other person who would generally write a tercet. Then, that 11-line poem would go back one last time to the other person to be completed. Then we’d move on to a new poem. Dean would send Simone a line

from a sonnet that would become the first line of the new poem, and we’d recreate the monster all over again.

The idea of using the sonnet to build the being of the poem appealed to us (though we try to avoid overtly famous lines), and in doing so, we are also considering “what exactly comprises a sonnet” and “what contemporizes a sonnet.”

One of the great things about poetry is its history of creative borrowing. Sampling has rather recently made its way into mainstream coolness, but poets have been sampling each other for centuries. In these collaborative pieces, we’ve stitched that tradition into the body of the poems

themselves.

Simone Muench & Dean Rader

This particular collaboration began in January 2013. Initially, we contemplated several ideas including a correspondence-type of collaboration in which we would trade individual poems; however, we wanted our voices intertwined in a way that would be indistinguishable to the reader: neither a Rader voice or a Muench voice, but a new third-bodied utterance spawned by differing styles. We elected on assembling the poems stanza by stanza, using this more integrative approach in an effort to co-join the presumed chaos of collaboration with the formal constraints of the sonnet. Because collaboration is frequently perceived as chaotic and can often suffer, as the luminary Michael Anania notes, from the “bipolar diffusion or poetic jiu-jitsu contending egos can produce,” we resolved to work within the framework of a highly structured form—specifically, the sonnet.

We refer to our poems as "Frankenstein Sonnets" because we cut lines from other poet’s sonnets, then graft our own sonnets onto the originating skein of flesh. When we first decided that Frankenstein would be the umbrella concept for our sonnets—the suturing together of other’s flesh/words with our own—we addressed how much should be cannibalized and how much should be our own. We ended up being minimally cannibalistic, deciding only to swap lines from other people’s sonnets to employ as the first line (which also serves as the title). So, for example, Simone would provide Dean with a line and we would then write the first stanza initiated by the provided line, thus establishing the first rhyme set as well as the type of sonnet, before forwarding it to the other person who would complete the second quatrain and then send it back to the other person who would generally write a tercet. Then, that 11-line poem would go back one last time to the other person to be completed. Then we’d move on to a new poem. Dean would send Simone a line

from a sonnet that would become the first line of the new poem, and we’d recreate the monster all over again.

The idea of using the sonnet to build the being of the poem appealed to us (though we try to avoid overtly famous lines), and in doing so, we are also considering “what exactly comprises a sonnet” and “what contemporizes a sonnet.”

One of the great things about poetry is its history of creative borrowing. Sampling has rather recently made its way into mainstream coolness, but poets have been sampling each other for centuries. In these collaborative pieces, we’ve stitched that tradition into the body of the poems

themselves.